A Unique Performance Optimization for a 3D Geometry Language

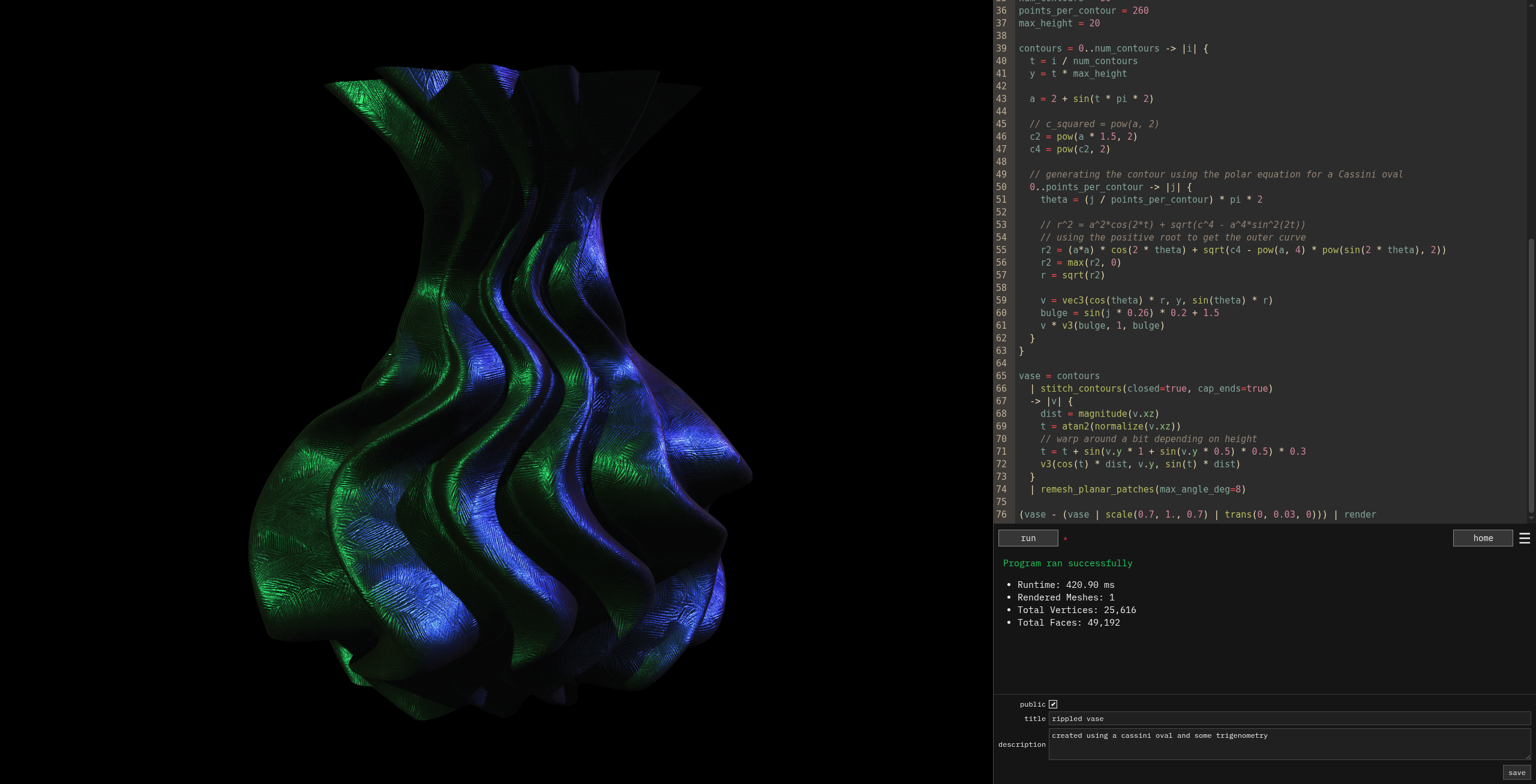

For the past several months, I’ve been working on a programming language called Geoscript. It’s specialized for generating and manipulating 3D geometry for use in a Shadertoy-inspired web app called Geotoy.

Geoscript uses a pretty simple tree-walking interpreter for its execution. That being said, I’ve put in a decent amount of effort optimizing it for runtime speed as well as building up an optimization pipeline for the language itself.

But first, let me give a little background on Geoscript’s optimization pipeline to give some history and context.

(or just skip to the “Cross-Run Expr Cache Persistence” section below if you want)

Geoscript Optimization Pipeline⌗

The first optimization I added for geoscript was basic constant folding. Nothing special or unique so far; just the usual approach of finding things like { op: Add, lhs: Literal(1), rhs: Literal(1) } in the AST and replacing it with Literal(2). I got the initial version working pretty quickly and started extending it to support more operations and data types. As I continued, I quickly came to realize something:

Unlike programs from other languages, Geoscript doesn’t accept user input, perform DB calls, or interact with any external system at all. There are some small exceptions to this like PRNG calls and side effects to render meshes or print debug messages. But since the RNG is seeded, a Geoscript program is really just a pure function with zero arguments; it produces the exact same output every time it’s run.

Because of this fact, once I made the constant folding smart enough, it turned out that most or even all of the program would end up getting ran during the “optimization” process. This even applies to closures, as long as the variables they capture from the outer scope are themselves constant (it took some pretty complicated plumbing to get that part working correctly). The AST would often get replaced with just render(precomputed_mesh_literal).

Despite this, there weren’t really any significant user-visible changes to the way the language/interpreter worked, and there weren’t very dramatic speed-ups to program execution. The optimizations did enable some speedups for cases like this though:

spheres = 0..1000

-> || {

# random `vec3` where each element is in the range [-1000, 1000]

pos = randv(-1000, 1000)

s = icosphere(radius=10, resolution=4)

s | translate(pos)

}

| join

In that case, the s = icosphere(...) statement doesn’t depend on any input in the closure or anything other than its literal arguments. So, the constant folding will replace it with a literal mesh in the AST. This saves the sphere mesh from having to get re-created each iteration of the loop and also saves on memory since the underlying mesh representation is reference-counted and translate just updates the transform matrix without mutating the mesh’s geometry itself.

Anyway, once I got the constant folding mostly wrapped up, I moved on to trying to add some other optimizations to the pipeline. The optimization I chose to pursue next was Common Subexpression Elimination, which is commonly referred to as CSE. This involves identifying identical expressions in the AST and replacing them with a single instance in a variable. This saves the value from having to get computed multiple times and can also unlock further optimization opportunities.

The first thing you need to do when implementing CSE is to set up a way to determine if two expressions (AST sub-trees) are identical. The approach I used for that is tree-based structural hashing, which I’m pretty sure is the standard solution. It was a little fiddly and tedious to set up, but I eventually got it working so any arbitrary AST could be deterministically hashed to a unique u128.

The next step I planned for implementing was to walk the AST, hash each node, identify duplicates, and replace them with references to a new temporary variable I’d create. This would require consideration for scopes and context, but if implemented correctly it would yield effective intra-expression CSE.

I also wanted to see if I could implement inter-expression, full-program CSE. For example, I wanted to be able to handle cases like this:

s = icosphere(radius=10, resolution=4)

some_fn = || {

// ...

another_sphere = icosphere(radius=10, resolution=4)

// ...

}

Ideally, the CSE pass would identify that those two icosphere expressions were both identical and replace them both with a reference to the same pre-computed mesh. This would only work for fully-const cases. So if the radius of another_sphere depended on an argument of some_fn, for example, this optimization wouldn’t apply.

So each time an expression is evaluated, it’s hashed and the resulting value is inserted into the memoization cache. The next time an identical expression is hit, we get a cache hit and instead of running the interpreter we just clone the value out of the cache and use that.

Cross-Run Expr Cache Persistence⌗

It was at this point that I suddenly had a very exciting idea:

Geotoy, Shadertoy are essentially live-coding environments. As a developer working in them, you usually iterate by making one small tweak or addition, re-running the code to see the updated output, and then evaluate based on that what to change next. The vast majority of the program usually stays exactly the same. By making the constant expression cache persistent, we can just re-use the results from the previous run for all the unchanged portions of the program.

In some cases this isn’t going to provide a lot of benefit. If you change a variable on line 1 which is depended on by every other line after it, there will be no cache hits and this strategy won’t provide any value. However, in very many real cases, a very high percentage of the program’s runtime can be cut out.

Here’s an example from a real Geotoy composition I was working on:

distance_to_circle = |p: vec3, radius: num| {

sqrt(p.y*p.y + pow(sqrt(p.x*p.x + p.z*p.z) - radius, 2))

}

radius = 8

0..

-> || randv(-radius*1.1, radius*1.1)

| filter(|p| distance_to_circle(p, radius) < 2)

| take(1550)

| alpha_wrap(alpha=1/100, offset=1/100)

| smooth(iterations=2)

| simplify(tolerance=0.01)

| render

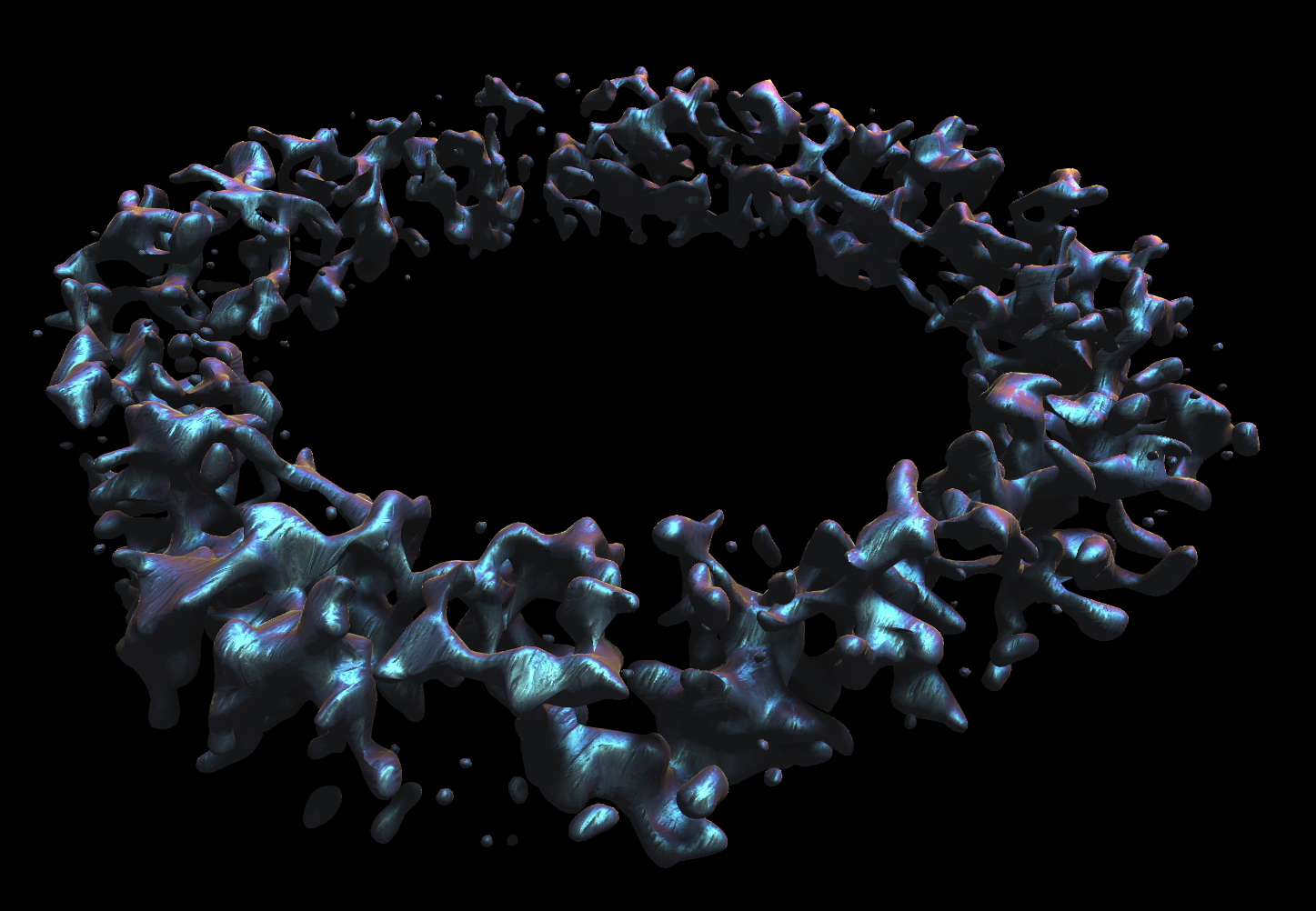

alpha_wrap is a function from the CGAL library which works kind of like a sophisticated “concave hull” algorithm. It generates a mesh that encloses a set of arbitrary 3D points. It’s used for repairing meshes with bad or incomplete topologies and for things like processing LiDAR point cloud data. I’ve found that it’s also extremely useful for generating really cool-looking organic shapes from procedurally generated point clouds:

The downside of this function’s power and versatility is that it’s very expensive to run. On my computer, that alpha_wrap call takes around 900ms to run. The more points you pass and the higher you turn up the detail level, the bigger this gets as well.

Now, consider a case where you’re just tuning the tolerance param of the simplify function, trying to find a good balance between mesh quality and vertex count. Previously, this would require re-running the entire program each time - including the expensive alpha_wrap call - even though its output remains exactly the same. With the persistent expression cache, that whole part of the AST will just get pulled out directly and only the changed simplify() call gets run.

Unsurprisingly, this translates to huge reductions in execution time and dramatic improvements to the developer experience working in Geotoy:

PRNG Handling⌗

One thing you may have noticed in the source code for that composition is that there’s a conspicuous randv call right at the beginning of the pipeline. Since this call both mutates the RNG’s state as well as relies on its hidden starting state, you might think that this would end up making the whole thing impure and non-const. And you’d be right.

This is something I had to handle explicitly in my expression cache in order to make caching it possible. A large number of Geotoy compositions make use of RNG calls, and just turning this optimization off for all those cases seemed like a big waste to me.

This essentially treats those expressions as pure functions of (rng_state) -> (T, new_rng_state) instead of the usual () -> T for most const expressions. Since RNG is re-seeded each run and the PRNG is fully deterministic, this means that as long as everything runs in the same order, the PRNG will transition to the same states after each call and the expression cache will be hit successfully on subsequent runs.

Conclusion⌗

This persistent expression memoization optimization has ended up becoming the most impactful optimization I’ve added to Geoscript by far. It’s pretty funny since I came up with the idea for it completely out of the blue while working on CSE, which I haven’t even bothered finishing up yet.

That being said, this is obviously in no way a completely novel idea I’ve invented here. In fact, it very closely models the kinds of caching techniques used to speed up build systems like Nix and Bazel. Instead of caching object files or software packages, it’s caching the intermediate values produced while evaluating a program’s AST. This approach is just uniquely suited to Geoscript/Geotoy’s use case, where the same program is run repeatedly with small changes and no external or dynamic inputs.