Building a Signal Analyzer with Modern Web Tech

I recently spent some time building a browser-based signal analyzer (spectrogram + oscilloscope) as part of one of my projects. I ended up using some very modern browser APIs and technologies that I'd not worked with before, and I discovered a lot of really interesting patterns and techniques that I'd never seen before in a web app.

This inspired me to write about the individual APIs that I used, how and why they were useful for the project, and some interesting patterns they facilitate for building complex multi-threaded applications in the browser.

Background

I've been working on a web-based digital audio workstation on and off for the past few years. It started as a collection of experiments with audio synthesis in the browser, and it has slowly grown into a cohesive platform for working with audio and producing music.

I've built up a pretty substantial collection of modules for generating and manipulating audio, but one thing that was lacking was the ability to visualize audio and other signals within the app. Specifically, I wanted to build a module that contained a combined oscilloscope and spectrogram — that would allow simultaneous time and frequency domain views into signals.

Besides being useful for debugging during development, these tools are important when mixing and mastering tracks. As the platform is maturing, these parts of the music-making process have been growing in importance.

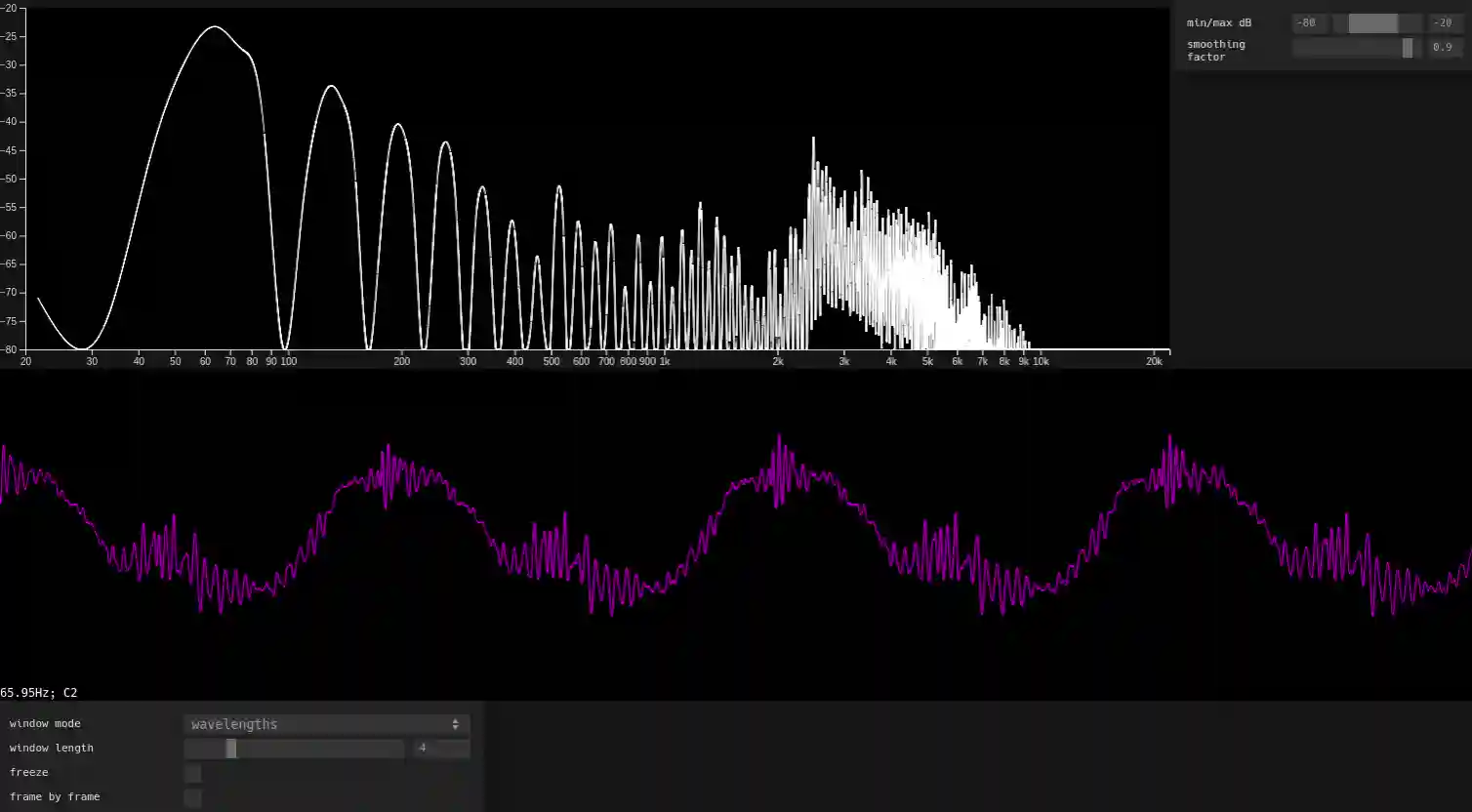

Here's what the signal analyzer ended up looking like when integrated into the main web synth app:

And here's a demo showing it in action (looks best on desktop): https://synth.ameo.dev/composition/102

The white visualization on top is the spectrogram. It plots the power of the input signal at different frequencies, and it updates live as the signal changes over time. It's a very useful tool when mixing multiple signals together or when performing heavy processing on signals since it helps identify imbalances in the spectrum, spot artifacts or undesired frequencies, and things like that.

The pink visualization on the bottom is the oscilloscope. It plots the actual waveform of the audio signal as it is played, essentially creating a live line plot of the signal's samples. It's very useful for debugging issues with synthesizer modules or other audio generators, and it's also useful for analyzing phase relationships between multiple signals.

Tech Stack

The interesting part of this work is the usage of very modern web tech to power it.

This was my first time trying out some of these features, and I was extremely impressed with the new patterns and capabilities they unlock. I really believe that this latest round of new APIs and capabilities enables whole swaths of new functionality for the web that were either impossible, difficult, or inefficient before.

Multi-Threaded Rendering

In 2023, every device running a browser has anywhere from 2-64 cores or more, and it's high time they're made use of them for all our applications. The majority of the new browser APIs used here facilitate or otherwise relate to running code on multiple threads in the browser.

Even though the core audio processing code of the application runs on a dedicated audio rendering thread via Web Audio, it's still important to keep the UI responsive so that user inputs aren't delayed and interacting with the app is smooth and jank-free.

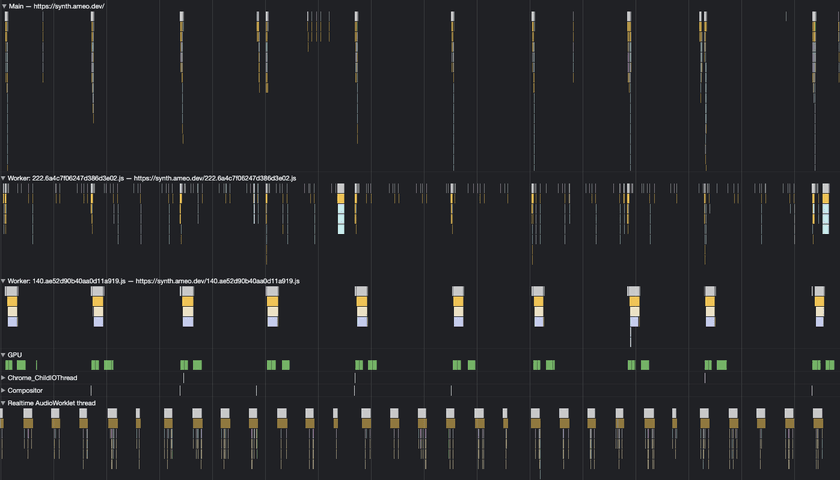

Here's a screenshot of the Chrome dev tools showing a profile of the signal analyzer while in use:

As you can see, the work is spread across 4 different threads, plus the GPU. The main thread is at the top and has an extremely light load - less than 5% of one core. All the heavy lifting is done by the dedicated worker threads for the visualizations and by the web audio rendering thread itself at the bottom.

Web Workers

The main way to run work on multiple threads on the web is Web Workers. They can be used to run arbitrary JavaScript and are limited in that they can't manipulate or access the DOM. They can communicate with other threads, including the main thread, using a message-passing interface as well as some other methods which I'll get into later.

For the signal analyzer, both the spectrogram as well as the oscilloscope each run in their own web worker. Web Workers actually have been around for a while and have some nice tooling built up around them, but making use of them was often a pain in the past.

When I tried out web workers on a previous project, I had to install special Webpack plugins and use other hacks to get them to work. Even then, I could never get TypeScript support working properly. I ran into issues where importing code in my project from a worker would cause them to fail to load in some browsers.

Today, the situation is greatly improved:

A big part of this improvement is a great library I discovered called Comlink. It makes initializing and communicating with web workers very easy by wrapping the message channel in a TypeScript-enabled RPC interface. Rather than dealing with sending and receiving paired messages, you just call a function and await a promise.

Another big change is that web workers are now natively supported by popular bundlers like Webpack, which I use for web synth. It allows workers to be written in TypeScript, share types between the worker and other files in the project seamlessly, and import workers from other files directly:

const worker = new Worker(new URL('./Spectrogram.worker', import.meta.url))It's a whole different story compared to when I first used them. They feel much more like a mature feature that can be depended on rather than an experiment only applicable to some niche use cases.

SharedArrayBuffer

This is another case of a feature that's been around for a long time but improved recently.

SharedArrayBuffer is JavaScript's solution for sharing memory between threads. It works just like a regular ArrayBuffer, but it can be sent to other threads via message ports.

For the signal analyzer, SharedArrayBuffers are used extensively to exchange data between different threads in the application. They are used by the oscilloscope to provide raw samples from the audio rendering thread to the oscilloscope's web worker, and they are used by the spectrogram to transfer FFT output data from the main thread to the spectrogram's web worker.

When data is sent through a message port such as the one belonging to a web worker, all the transferred data must be cloned (except for a few special cases where it can be transferred and made no longer available on the sender thread). If the sent data is short-lived, it will also need to be garbage collected at some point. If the receiving thread is latency-sensitive, such as the audio rendering thread, this can cause problems like buffer underruns.

With SharedArrayBuffer, data can be truly shared between two threads. Both threads can read and write to the same buffer without having to transfer it back and forth. There is some synchronization necessary to prevent data races and and other bugs, though, and that is handled by...

Atomics

Atomics are a set of functions provided for performing atomic operations on shared memory. They cover many of the commonly used operations like store, load, add, and compareExchange to support threadsafe reads and writes. They also support a semaphore-like API which allows one or more threads to block until some other thread wakes them up.

Atomics have been supported in the major browsers for 2 years or more. However, there is a new function - Atomics.waitAsync - which was only supported by Chrome until quite recently.

Atomics.waitAsync

Atomics.waitAsync is similar to the existing Atomics.wait API but instead of blocking the thread, it returns a promise that resolves when the notification is received. This greatly expands the power of atomics for synchronization and is even allowed to be called on the main thread (Atomics.wait can only be called in web workers).

Atomics.waitAsync.

Atomics.waitAsync is very useful for the oscilloscope since it needs to be able to wait on multiple event types at the same time. It needs to listen for new blocks of samples to be produced by the audio rendering thread and at the same time, it needs to be able to run callbacks from requestAnimationFrame.

Since Atomics.wait is a blocking call, the animation callback will not be able to fire until the Atomics.wait call finishes and the event loop is manually yielded with await new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, 0)) or similar.

Atomics.waitAsync avoids this issue since it doesn't block. While await Atomics.waitAsync(...) is called, the thread is free to handle animation callbacks and other microtasks as soon as they're received.

Atomics.waitAsync, so I have slower fallback code using Atomics.wait included as well.

They are considering it, though, and it will hopefully be available in all major browsers soon!

OffscreenCanvas

OffscreenCanvas is another new API that now works in all major browsers since the Safari 16.4 update. It allows for a canvas's rendering context to be transferred off the main thread to a web worker which can perform the work related to the rendering there and then render to it directly using WebGL, Canvas2D, and other methods.

Without OffscreenCanvas, it's still possible to implement the rendering logic in a web worker in some cases. In the past, I've used the pattern of rendering into a pixel buffer in a web worker, transferring that buffer to the main thread via message the message port, and then drawing it to the canvas with putImage. This works, but it adds latency and still forces the main thread to do the work of writing that data to the canvas.

OffscreenCanvas allows for true multi-threaded rendering to canvases. Once the OffscreenCanvas is created and transferred to the worker, the worker can take over completely. The browser handles all the details of synchronizing calls to the GPU and compositing pixel data together in sync with the monitor's frame rate.

Wasm SIMD

I've made extensive use of WebAssembly SIMD in the past on web synth and other projects. It's incredibly cool to me that it's possible to write SIMD-accelerated code that runs sandboxed in the browser, and I love working with this tech.

However, I've always had to do the annoying work of maintaining and shipping a non-SIMD fallback version of the Wasm to work in browsers that didn't support it yet. Safari was the last major browser to lack support, and with the 16.4 release that's no longer necessary!

Wasm SIMD is used in some of the rendering code for the spectrogram as well as in the implementation of biquad filters which are used by a band splitting feature for the oscilloscope I'm working on. It greatly accelerates aspects of the visualizations, making it possible to render in higher quality and consume less CPU.

WebGPU

WebGPU just made it out to stable Chrome last month, and it predictably created quite a stir in the web graphics community. It's only available in Chromium-based browsers currently, I expect to see it make its way out to others in the next months/years.

People are already using features like render bundles to do things that were impossible before even with WebGL.

Although I didn't use WebGPU for this project, I felt it's worth mentioning. I definitely am looking forward to working with it in the future.

Architectures

These new APIs are very useful on their own in some cases, but their real power shows when they're used together. This was my first time using the full suite of these features and I was extremely impressed with the kinds of patterns they facilitated.

Spectrum Viz

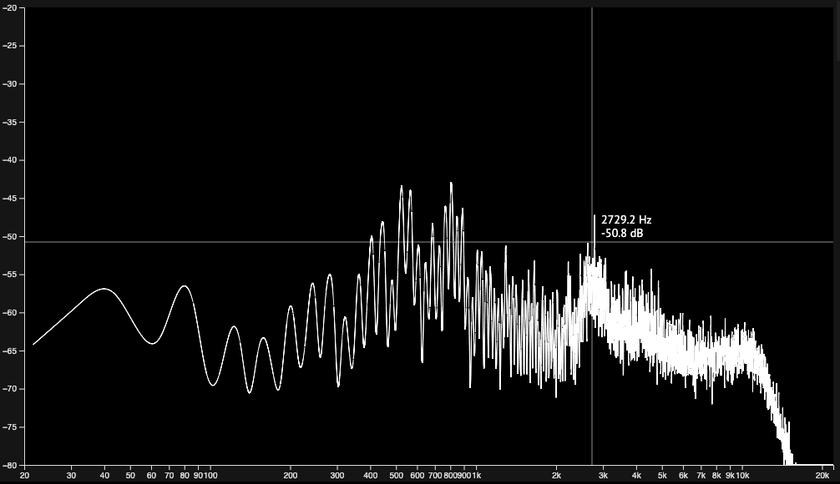

Here's a diagram showing how the web worker for the spectrogram initializes, renders, and communicates with the main thread:

One interesting thing to note is that the animation loop is actually driven by the main thread while the rendering itself all happens in the web worker. This is because all interaction with the Web Audio API needs to happen from the main thread, including using AnalyserNode to retrieve frequency domain data.

It would technically be possible to use raw samples instead and perform the FFT myself, but that would be much more complicated and less efficient. The browser's implementation uses a heavily optimized FFT implementation along with fancy windowing functions and other advanced features. I opted to go with the native approach, even though it means running a small bit of work on the main thread.

Also note that while SharedArrayBuffer is used to exchange the actual FFT output data with the worker, the async message port interface is used to handle initialization and runtime configuration. It enables structured data like JS objects and whole ArrayBuffers to be easily exchanged between threads, and it provides a fully typed interface to do so which is a huge boon to developer experience.

Oscilloscope

For the oscilloscope, raw samples are needed directly from the audio thread so the architecture is a bit different:

Lots of data moving between threads, but it's the same methods as before: SharedArrayBuffer for rapidly changing data (raw audio samples in this case) and message port for structured event-based data.

To get access to the stream of live samples from the audio thread, the oscilloscope creates an AudioWorkletProcessor. This is a new-ish Web Audio API that allows user-defined code to run directly on the audio thread. They're used extensively by the rest of web synth to implement synthesizers, effects, MIDI scheduling, and pretty much everything that deals with audio.

But in this case, the AWP's sole purpose is to copy the samples into a circular buffer inside a SharedArrayBuffer which is shared with the web worker. Once it finishes writing a frame, it notifies the web worker which then wakes up and consumes the samples.

One difference between the oscilloscope and the spectrum viz is that the consumption of input data is separated from the rendering of the viz itself. Web Audio uses a frame size of 128 samples, meaning that at the sample rate I'm using of 44,100 samples/second there will be ~344 frames processed by the AudioWorkletProcessor every second.

This is well above the frame rate of pretty much every device. Plus, there's no guarantee that the frames will arrive evenly spaced in time since audio is buffered to avoid missed frames.

So, the viz builds up its internal state incrementally every time an audio frame is processed and only renders it once the requestAnimationFrame fires. The use of Atomics.waitAsync allows for both of the loops to run concurrently on the same thread. Without it, it would be necessary to do the short manual timeouts and yields like mentioned before or the requestAnimationFrame callback would never fire.

Seamless Integration of Rendering Methods

One thing that's easy to take for granted as a web developer is how well the various rendering APIs that browsers have compose with each other.

In the larger web synth project, I have UIs built with WebGL, Canvas2D, SVG, HTML/DOM, as well as Wasm-powered pixel buffer-based renderers all playing at the same time and working together. The browser handles compositing all of these different interfaces and layers, scheduling animations for all of them, and handling interactivity.

For the oscilloscope, I built a UI on top of the viz itself which contains scales and labels for the axes as well as a crosshair that displays the values at a hovered point. It's built entirely with D3 and rendered to SVG. There was no special handling needed — just append the SVG element to the DOM, position it on top of the canvas with CSS, and render away.

Device-Specific Handling

Another aspect of this which is easy to take for granted is the browser's handling for high DPI and high frame rate displays.

There is a small bit of handling needed to detect the DPI of the current screen and using it to scale your viz, but it really just consists of rendering the viz at a higher resolution and then scaling the canvas it's drawn to. The whole thing is like 20 lines of code. The browser takes care of making it show up nicely the subpixel rendering.

In comparison, implementing high-DPI rendering in a native UI framework like QT5 looks... rather more difficult.

Rendering to high frame rate displays works out of the box. The requestAnimationFrame API handles scheduling all the frames at the right times with no configuration needed. It even handles scaling the frame rate up and down when I drag my browser window between my 144hz main monitor and my 60hz side monitors.

Conclusion

As these new APIs have rolled out in various browsers over the past few years, I've read the announcement posts and checked out toy examples that make use of them. They were interesting and relatively exciting, but it all seemed like a random smattering of APIs that were each suited to some niche use-case. The fact that they mostly came out one by one over such a long period of time contributed to that feeling as well.

It wasn't until I built this signal analyzer and made use of them all together that I was able to recognize the bigger picture. It really feels like the working groups and other organizations behind the design of these APIs thought very hard about them and had this vision for them from the start.

It really feels like a platform rather than a random collection of APIs hacked together on top of a document renderer.

In the past, the vast majority of opinions I've heard from people (especially tech people) about web apps is that they're slow, janky, buggy, and bloated. Looking back, it's clear why this was the case; I've probably spent days of my life waiting for various electron apps to load myself.

It's my hope and belief that it will soon be easier to build high-quality web apps that users love than native apps for the majority of use cases. I'm very excited to continue working with these APIs and pushing the envelope further on what can be done on the web.